Tucked away in the remote valleys of the Lake District, hidden from the bustle of towns and roads, lived a rare breed of solitary figures – men and women who chose isolation over society. Among them were hermits, recluses, and those whose lives balanced on the edge of eccentricity and obsession. Their stories, often glimpsed only through local gossip or archival records, reveal a fascinating intersection of resilience, madness, and human curiosity. One such figure was John Campbell, the Woundale Hermit, whose lonely life in the fells would eventually bring him to the attention of the courts and medical authorities.

Richard

<<>>

Recluses

Following the death of Ada Raynor in Battersea, the following article appeared in the Lakes Herald. Although Ada was regarded as a “very wealthy” woman, she was found in her home dying of starvation, having lived a sad and lonely existence with only a butcher’s boy to run her errands.

“The pathetic death of a recluse, known only to an errand boy for years, brings to mind the few cases of the kind known in recent years, and points to the gradual disappearance of this species from our civilisation. In former times, folk who retired from the eye of even their near neighbours were much more numerous; but nowadays one hears seldom about them. There was an instance in Chelsea a year or so ago, and now and then reports come from other parts of the country – for example, from Hertfordshire, where a rich man lived alone for many years, and even had a public road diverted at his own expense to keep his fellow-creatures the further from his retreat.

In our own Lake District we have had the Skiddaw Hermit, and even now there is the Woundale Hermit, who lives his lonely life amidst the ‘cheerful silence of the fells’ within a few miles’ reach, however, of Ambleside and Troutbeck, and all his earthly wants. Yet, though the public hear little of the cases that still exist, and though those cases have diminished, there is scarcely a town without some hidden resident, and many villages up and down the land have their mysteries.

There is a tiny market town in Herefordshire where, till recently, an old woman dwelt in a house unseen by anybody for a score of years. The front door was never opened, the windows were never uncovered. Her food was passed in through a pantry window. Of clothing she bought none. There was a shop in the house full of articles of her deceased husband’s stock-in-trade; but they were never touched. How does such a solitary soul exist? It is a very different kind of existence, this within four walls, from that of the men who retire into the heart of the moors or the mountains, or the forests, and win food and clothing by the exercise of their skill over wild animals. These live more or less healthy lives. They who fasten all the inlets of fresh air, and dwell in what can be called nothing but vaults, must have a miserable existence. They are worse than useless; they are often centres of the diseases that arise from uncleanliness. Their abodes ought to be opened by the sanitary officers for the sake of those who dwell near them.”

Lakes Herald – 1st September 1911

I first came across the story of the Woundale Hermit while researching another tale connected with the Lake District town of Ambleside. As is often the case when delving into the depths of the archives, it is very easy to be side-tracked by other fascinating Lakeland stories. It wasn’t just the fact that I had never heard of this “recluse” that intrigued me, but also the location and the period, which fascinated me most of all.

While many recluses remained largely unknown to the wider public, their lives reflected very different forms of solitude. Some, like the woman in Herefordshire, withdrew entirely behind closed doors, leaving their existence barely noticed. Others, like the Lake District hermits, chose the open spaces of the fells and valleys, sustaining themselves through skill, resourcefulness, and occasional interaction with local communities. Among these latter figures was John Campbell, the Woundale Hermit, whose secluded life combined remarkable self-sufficiency with troubling delusions – ultimately bringing him to the attention of the courts and medical authorities.

<<>>

Victim of Strange Delusions

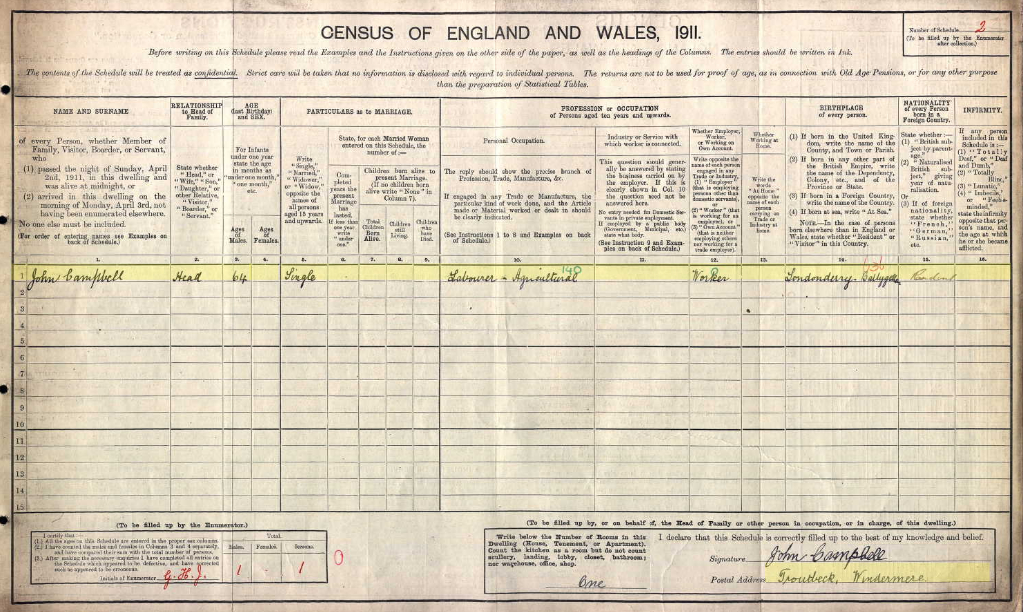

On Tuesday, 8th June 1915, at the Police Court in Ambleside, John Campbell, aged 68 and known locally as the Woundale Hermit, was charged with being a “wandering lunatic.” Sergeant Taylor testified that at 4:30 p.m. the previous afternoon he had gone to Market Hill, where he saw Campbell, who approached him shouting and complaining. Earlier that day, Campbell had already visited the Police Station two or three times.

He claimed that a man had fired guns over his dwelling in Woundale at night and had also sent motor cars and charabancs to hunt him down, leaving him in constant fear for his life. He further alleged that this man had blocked the road from Troutbeck, was the leader of the revolutionary Catholics, and was conspiring with others to deprive him of food so that he would starve. Sergeant Taylor said he tried to persuade Campbell to return home, but Campbell refused, insisting he would not do so until the man had been arrested. At that point, Sergeant Taylor was obliged to take him to the Police Station.

Following the events at Market Hill, Dr. Johnston was called to examine Campbell, who was in a state of “great excitement” and appeared to be suffering from “religious mania.” Campbell accused a Windermere gentleman of leading a “great Papal rebellion” and, along with many others, of trying to take his life and blocking the Troutbeck road. Dr. Johnston stated that there were clear signs of insanity, and he was fully prepared to certify this. In his opinion, Campbell “ought to be under control” and should be “taken care of.” When given the chance to question the witnesses, Campbell did so – but his responses only reinforced their evidence of his insanity.

An order was then made for his removal to Garlands Asylum in Carlisle.

Before these events, Campbell had lived a solitary life in Woundale for 16 years. He was originally from Derry, and as a young man he had held a good position with a well-known publishing company. At the time of his arrest in Ambleside, he had a sister living in London, from whom Mr. W. W. Strang of Ambleside had received a letter that very morning. Mr. Strang had taken an interest in Campbell for many years and had been in contact with his sister in an effort to provide him with further support.

John was well known in Ambleside, where he would go to obtain a few basic necessities, but he was reluctant to let people approach his retreat in the remote valley. A few managed to gain his confidence and learned something of his history. Once at ease with visitors, he would talk for hours on political and religious subjects, demonstrating a remarkable memory. He often left his money and belongings in the lonely stone hut that he called home and wandered as far as Durham or Northumberland, always returning to find that nothing had been disturbed.

Apart from religious subjects – he was plagued by strong anti-Catholic views – he was regarded as an intelligent conversationalist and a well-informed man. Someone who knew him fairly well during his years of self-imposed exile described him as unusually knowledgeable in political history and able to recite passages from the speeches of Bright, Shaftesbury, and Palmerston.

One of his eccentric habits was to deliver sermons in a stentorian voice as he walked through the countryside. When he required the bare necessities of life, he would descend Kirkstone Pass into Ambleside or Troutbeck. In later years, he was even found preaching to the sheep on the fells, telling them of his supposed threat of impending starvation – though in reality he was not penniless. He occasionally worked for local farmers, cutting bracken and performing other tasks; he also had friends who supplemented his income with gifts. Yet, in his troubled state of mind, it was often against these very friends that he spoke so harshly.

True to his solitary and eccentric ways, his dwelling reflected his lifestyle. The stone hut consisted of a ground-floor room with a loft above. As there was no stair or ladder inside, the hermit would climb the wall and crawl through a hole in the floor to reach the heap of bracken on which he slept. At one point, a friend provided him with a modern bedstead and an easy chair, among other items, but after returning from a trip to Ireland he discarded them and reverted to his primitive bracken bed and a simple, backless chair.

John Campbell died in 1931, having spent the final 16 years of his life in Garlands Asylum.

<<>>

John Campbell’s Hut

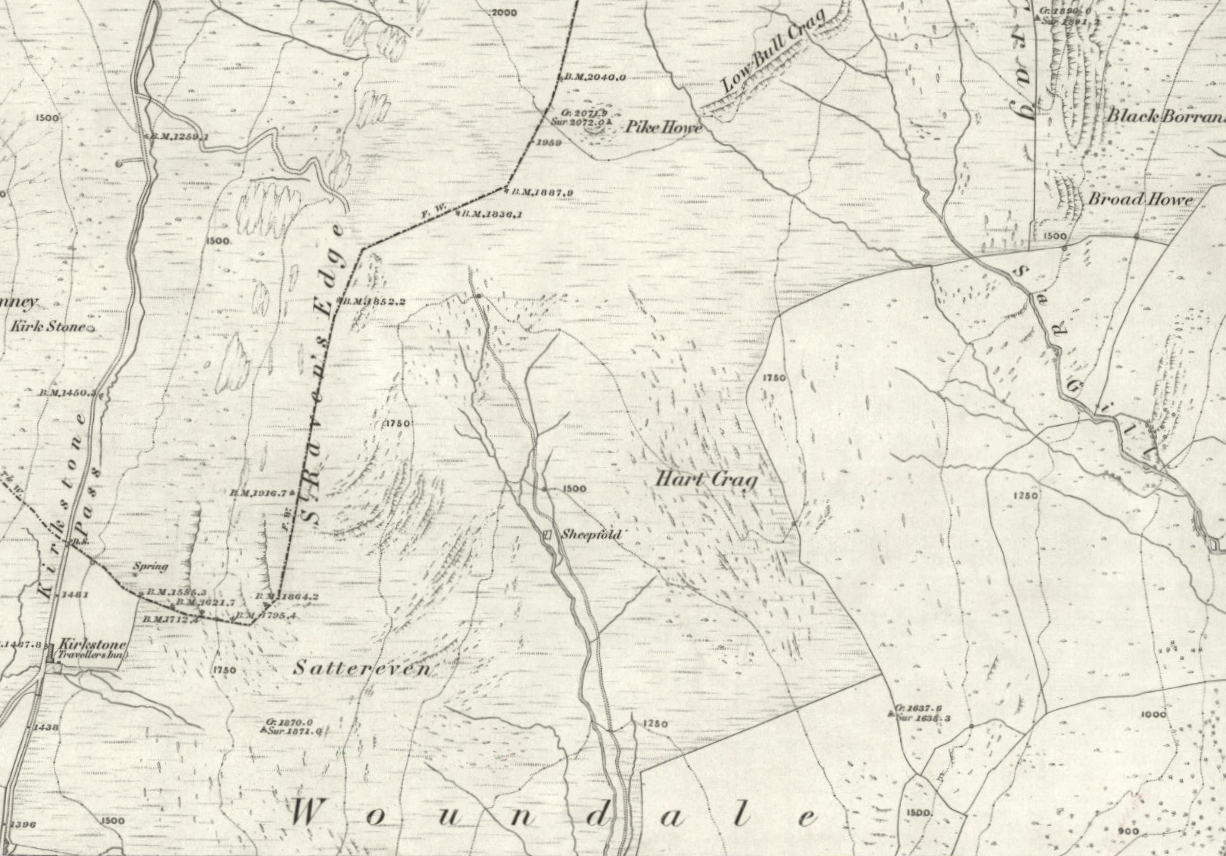

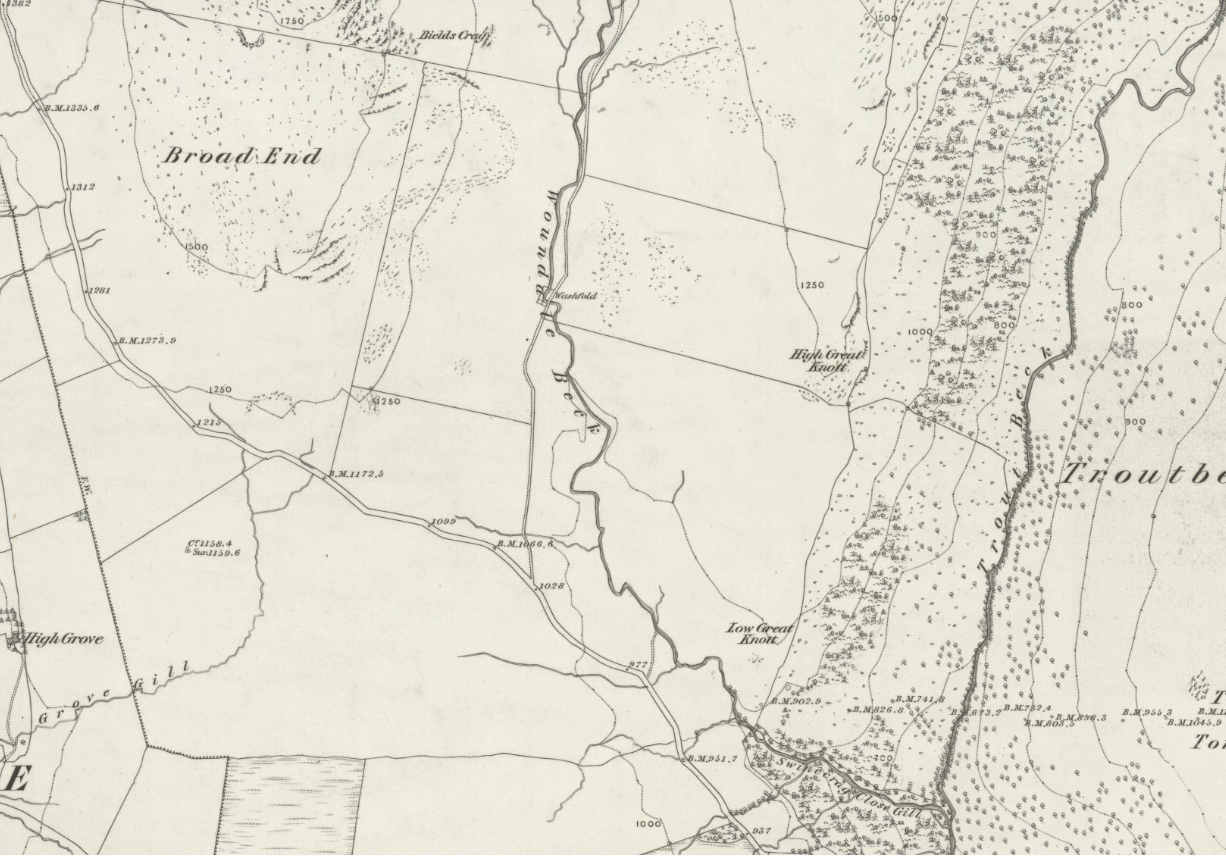

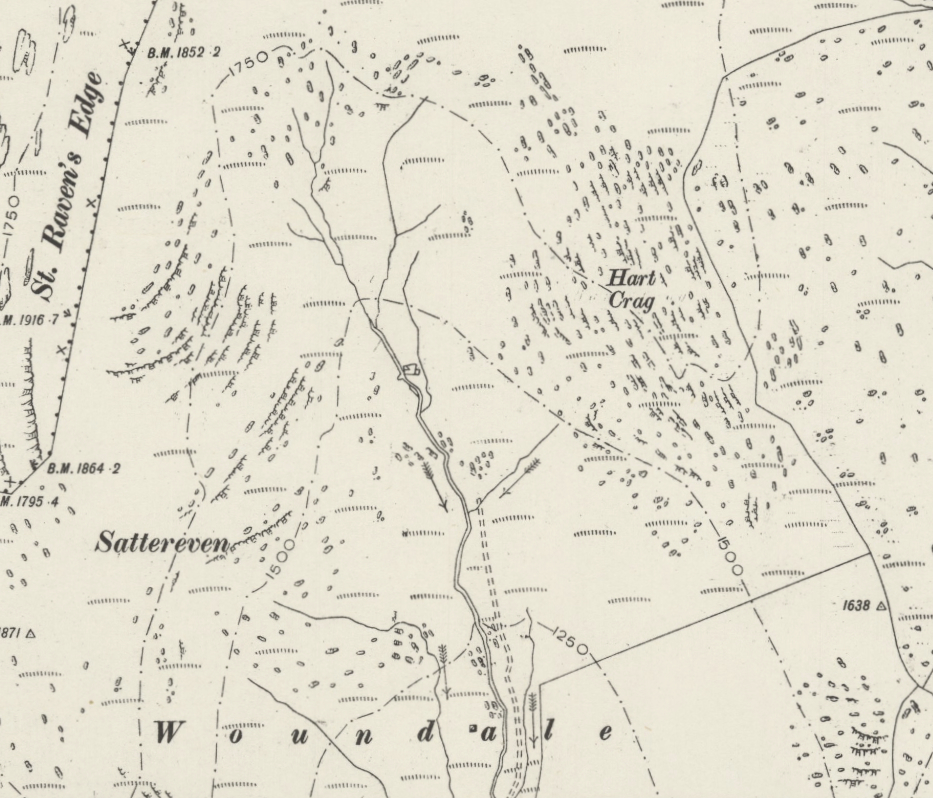

I wanted to learn more about the home where the Woundale Hermit spent the greater part of 16 years of his life. My search began with the Ordnance Survey maps of the 19th century, in the hope that they might reveal clues about when the stone hut was built and what its original purpose may have been.

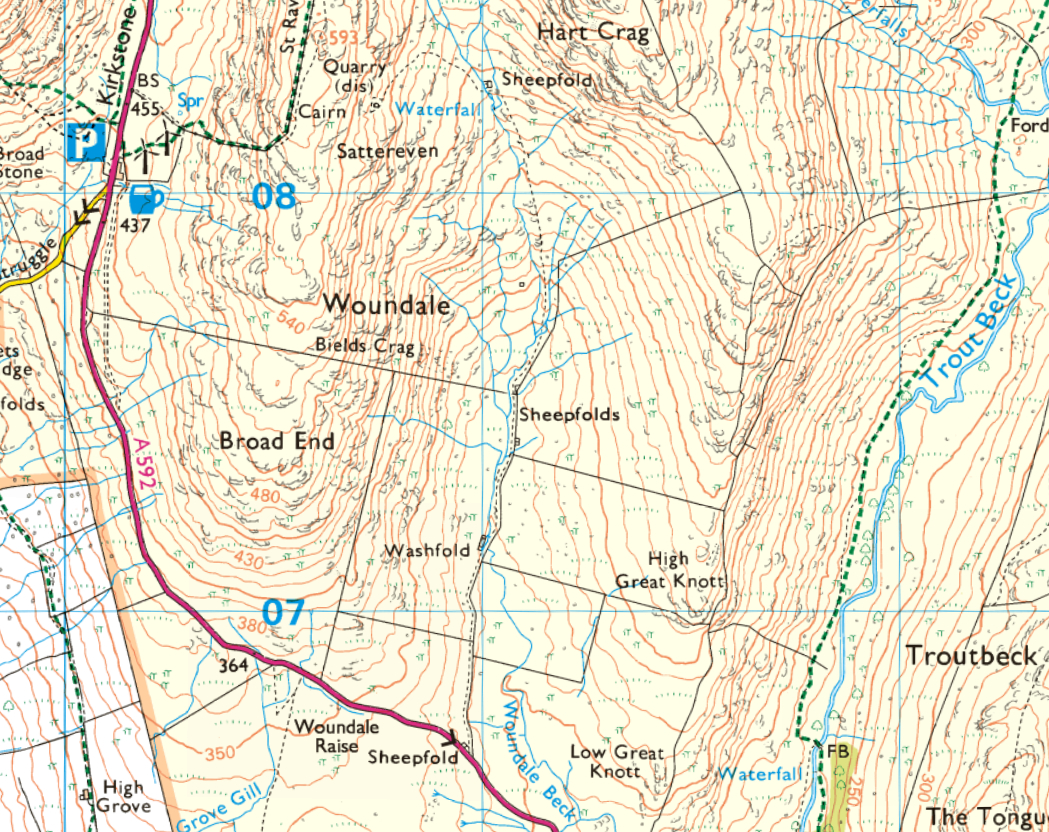

Woundale is a small, isolated valley a few miles north of both Ambleside and Troutbeck. Following the Inclosure Act of 1773, a “road” was commissioned in 1838 and marked out along this remote valley to improve access to the peat grounds at its head and to the upper reaches of Cauldale Moor. This road appears clearly on the Ordnance Survey map of 1859.

On the revised map surveyed in 1897, two points of interest stand out. Firstly, the peat road is much shortened, reaching only to the head of the valley basin. Secondly, a building appears next to the “a” in “Woundale.” As the 20th century approached, peat was likely falling out of favour, with both valley and town folk turning to other fuels. Collecting peat from the higher moors was therefore no longer essential.

Exactly when the hut was built remains something of a mystery, though it must have been constructed between 1859 and 1897. In my view, there are only two likely explanations for its existence: it was built either for drying peat or for drying bracken – or perhaps both. Its location is unusual, as it does not stand beside the road but instead lies awkwardly on the opposite side of Woundale Beck, which makes it seem more likely that it was intended solely for drying bracken.

It is now the middle of August 2025, a warm and hazy day in the Lake District. My wife and I parked at the top of Kirkstone Pass before making our way down the Troutbeck road to the foot of Woundale. Having studied the map the night before, we knew that a building still stood on the site, and we were eager to discover what condition it was in after all these years.

The beginning of the ‘road’ into Woundale. On the left are Broad End and Bields Crag, while at the head of the valley stands Hart Crag, with High Great Knott to the right.

Even after such a long spell of dry weather this summer, sections of the ‘road’ remain boggy, though they can be avoided.

The remains of the last visitor to the valley!

The impressive remains of an old sheep washfold beside Woundale Beck.

A three-spanned clapper bridge over Woundale Beck.

A closer look at the sheep dipping pool.

Hart Crag and the head of the valley from Woundale Beck.

John Campbell’s Hut comes into view on a tongue of land to the left of Woundale Beck.

We continued along the ‘road’ and crossed the gill at the same elevation as the hut.

Looking across, we could see that the south gable end of the hut was precariously leaning out. Given the amount of bracken in the area, you can see why a ‘bracken-drying hut’ would be located here.

John Campbell’s bathing pool, perhaps? Well, it was certainly deep enough for Tika!

Having negotiated the gill, we then had the bracken to contend with. I’m guessing that in John Campbell’s time, this would have been a lush green lawn.

We had arrived at John Campbell’s Hut. On the left is the main door, while on the right is the first-floor door. A timber ramp or earth bank would have been built below this door to provide access to the bracken-drying room.

It was wonderful to see that the fireplace and chimney were still intact. As with most old stone ruins, the floor level has risen due to rubble and many years of vegetation. I can just imagine John Campbell sitting in his chair by the fire in the depth of winter, ‘reciting passages from the speeches of Bright, Shaftesbury, and Palmerston.’

Looking at the south-east corner, we noticed a large crack in the stonework. This explains the leaning of the south gable. How many more winters can this wall survive?

The old floor beams have developed their own ecosystems!

Life persists, even in forgotten places.

“As time went by we drifted apart.”

The ground floor door frame.

A closer look at the crack in the south-east corner.

John Campbell’s view down the valley from the south window.

Looking across to the south gable from outside the first-floor doorway.

As we walked away from the hut, thoughts of John Campbell and his solitary life stayed with us. His story, though tinged with sadness, lingers on – the spirit of the Woundale Hermit remains in this quiet valley.

<<>>

Thanks, sources and further reading:

David Bradbury of PastPresented

National Library of Scotland

Ordnance Survey